Buzz – 1998

Jeanne Fay

June 1998

At 18, Christina Ricci, in The Opposite of Sex, turns up the heat.

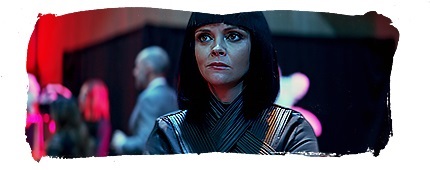

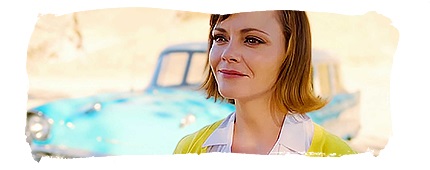

“I love to complain,” says Christina Ricci, pouring Diet Dr Pepper over her cigarette to put it out. “And this is the grossest shoot I’ve ever been on.” She’s been stuck in the middle of the Mojave Desert for the past week, filming night scenes on Desert Blue, a teen apocalypse movie. During the day, cast and crew all sleep at a Motel 6 with weak, sprinkly showers and tiny, chafing towels that’s right between Highway 14 and the train tracks. Ricci, a big star, gets her own room, although she’s been sharing it with her “friend,” an aspiring actor.

He, in turn, has been put to work shuttling actors too young to drive the 20 miles between the set and the motel. The shoot is plagued by local dune-buggy freaks tearing around and getting in shots. There’s one bathroom for everybody Ricci’s been doing her part to keep things gross–she’s been peeing in cups and tosing it out the window of her trailer. She eventually heads out to film her first scene of the day, standing patiently in a sand-whipping, eye-watering wind, waiting for someone to tell her what to do. Ricci, in chipped yellow nail polish and ample black eyeliner, seems easily a part of the environment, at home among the cheap motels and Burger Kings in this wasted patch of desert near the aqueduct. In this scene she giver costar Brendan Sexton III the finger as he roars by on a four-wheeler, screaming at her.

A visitor from the local film commission seems a bit aghast. “It’s hard to believe the little girl from The Addams Family is 18,” he murmurs. In the two weeks since her birthday, Ricci has had a series of revelations about how things change now that she’s 18. She gets her trust fund, roe one’ thing, and, she points out slyly, “I can have sex on camera now. Uh oh. Uh oh. Legally, that is–Ricci’s been doing plenty of bad-girl things on Camera for months. Like having head-slamming-against-the-wall sex in John Water’s Pecker, due out this fall. And seducing her brother’s boyfriend in Don Roo’s just-released The Opposite of Sex. And in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, “I’m on this acid trip and Benicio del Toro’s whipping me with a blanket and pulling me and trying to kiss me and I’m supposed to be 14 and strung out And I actually had to bite Johnny Depp’s ankle in one scene, and he was Like, ‘You can bite me really hard,’ and I was like, ‘There is no way I’m going-to bite you harder than that…”‘ Uh-oh.

If all you’ve seen of Ricci is her flawless turn as the lovable sourpuss Wednesday Addams, the half-dozen or so movies she has coming out in the next few months may be something of a shock. What exactly could the Desert Blue producer mean when, as Ricci’s flipping off Sexton and sauntering along grinning in her cropped sweatshirt, he whispers, “We wrote this role for Christina”! Not that Ricci has ever been the sweetie-pie type. She won her first role, in her school Christmas play, by goading Nicky, the little boy who had the part, until he punched her in the face. She then ran to the teacher to tattle–and Nicky’s role went to Ricci as his punishment. “I think he really thought he had done something wrong,” Ricci says. “I don’t know why he didn’t go to his mother and say, ‘That evil cunt!’ But he didn’t.” Nicky’s mother, an entertainment critic, came to the play anyway and, unaware of the cruel manipulation of her son, told Ricci’s mother to start taking her to commercial auditions. By the time she was 10, she had landed the role of Winona Ryder’s little sister in Mermaids.

And it was her very lack of moppety pertness that distinguished Ricci from the packs of little-girl actresses who always seem to be auditioning for Annie; it was her darkness and solemnity that led her to The Addams Family and its sequel. “I miss playing Wednesday; I would love to do another Addams Family movie,” she says. “And I didn’t have to act–that face is me, me when I’m really relaxed and not having to smile for anyone or talk.” “That face,” of course, is one of huge, judgmental eyes and a habitual frown. Wednesday allowed the young Ricci to explore her dark side, and even at 11, that is where she wanted to go. Meanwhile, her parents were divorcing, and her mom moved her and her three siblings from Montclair, New Jersey, to New York City, so Ricci could attend the Professional Children’s School and star in kids’ movies like Casper, Gold Diggers, and That Darn Cat.

These are credits she’d be happy to expunge from her record–movies she did because she “needed the money.” To watch her in these movies is to watch a perky sleepwalker; one is reminded of the scene in Addams Family Values in which she is forced to smile and slowly, slowly stretches her mouth into the most hideous and labored of grins. In counterpoint to her Professional Children’s classmate Macaulay Culkin, who even in his most murderous moments had an impish, I’m-just-a-kid innocuousness, Ricci looked like a girl who could hurt you. “When I was doing Casper, I was 14 and really into Reservoir Dogs,” she says. “Most directors are like, ‘Make it lighter, make it lighter, you’re not really that angry.’ I’m like, I’m not?”‘ There was little sign of Ricci’s depth of talent–and her subtly seething anger–until she took on the role of Wendy in last year’s Connecticut tragedy The Ice Storm. It’s a movie Ricci loves, but she’s modestly dismissive about her work in it. “I feel like I’ve been playing the same role my whole life,” she says, and it is indeed possible to draw Wendy/Wednesday parallels, to imagine the sexual awakening of Wednesday Addams happening this way, with little evidence of pleasure, just a kind of sickening curiosity. The I’11-show-you-mineif-you-show-me-yours scene in the bathroom was striking for the contrast between her plump little fingers unbuttoning her pants and her unswerving, half-excited, half-apprehensive gaze.

And, Ricci says, “It was the first movie I didn’t have to tape my tits down for” Rather than disappearing for a while, g la Jodie Foster, and reemerging all cleaned-up and confident, Ricci is pouring into her screen roles all the awkwardness and loveliness of her own transition from child to adult. She’s not afraid of–in fact, she almost revels in–making public the meanness and ugliness that adolescence inevitably entails. “I was so perverted when I was a little girl, and no one was going through that that I could see. The movie forced me to dwell in it; I was so depressed and could think only violent thoughts. I wanted to kill people. I think it would be such a relief for girls to see that movie, and see that other people feel like that, even though you’re not supposed to admit it.” It was much noted after Ice Storm’s release, although never with the cattiness that Alicia Silverstone endured, that Ricci had put on weight. “I got really sick for a while”–by which she means anorexic-“and when I got better I got really fat.” Nowadays, not overweight but decidedly voluptuous, she seems much more comfortable in her body; she’s irritated by actors’ endless discussions of weight and dieting and has no compunctions about eating a plateful of cheese ravioli for lunch. And while she loves dressing up and being cooed over for photo shoots, she has somewhat advanced feminist theories about eating disorders and cultural norms: “It’s all about male control over women, because they don’t want to deal with the mystery of a woman’s body. In her upcoming roles, Ricci’s not making much of a mystery of her own body.

Her now unbound breasts play a significant role in Vincent Gallo’s Buffalo ’66, due out this month. She plays a platinum-blond fantasy girl in glittery Dorothy tap shoes and an extremely tiny dress; when Gallo’s character takes her home to meet his parents, his father (Ben Gazzara) keeps grabbing at her, pulling her close in a mock fatherly hug that plants his face squarely in her chest. Ricci plays it simultaneously uncomfortable and amused. And “The Opposite of Sex is all about my cleavage,” she says. “Don would look at me and say, ‘Look at look at those tits!”‘ Asked why he cast Ricci, Roos doesn’t mention her cleavage, but he does remark on her ability to express both a knowingness beyond her years and a glowing, youthful purity, a synthesis of the traditional conceptions of young actresses as vapid ingenues or as dirty-minded, deliberate Lolitas.

This is where Ricci has found her niche, never begging for affection but always getting it anyway. Her character in Opposite is utterly and willfully unsympathetic, at least superficially: She’s a homophobic, backstabbing child-hating, foulmouthed, manipulative thief, and Roos says Ricci never shied away from that. “Other people worried about it, but Christina never did,” he says. “She was smart enough to know that all that didn’t actually make the character unsympathetic.” She cultivates this up-front, like-it-or-not attitude in person as well; she got in trouble recently for telling a magazine interviewer she thought incest was natural. Of course, she had a much more complex argument than that, but that’s what it got boiled down to. “I didn’t realize what I was saying,” she explains. “I didn’t mean that it should happen, I just meant that it was one of those things in human nature that was just there; men just want to sleep with young, beautiful girls. And in their minds there’s a difference between their daughter and another girl, but not in their bodies.

I was trying to explain all that, but all that came out was that ‘incest was totally natural.’ And then I realized that that was an awful thing to say and I was like, Oh no, now everyone thinks I’m an incest fiend and want to have sex with my children or something.” She also has a spiel she likes to give about the necessity of violence in films and television (“Can you imagine never having seen violence on TV and going to New York and seeing some guy get stabbed in the ear! You’re gonna fucking have a breakdown!”), refers to her animal-rights-and-vegetarian phase as “repulsive,” and admits easily that she and her (similarly underage) friends hang out in bars in New York. “I probably wasn’t supposed to say that,” she reconsiders. “But I couldn’t think of a lie.” This is–and she knows it–what separates her from the other young actresses with whom she is usually compared and often competes.

(The elegant Natalie Portman was reportedly up for Wendy in The Ice Storm but was scared off by the material; Ricci was desperate for the role Claire Danes won in Romeo + Juliet.) And she knows that creating and maintaining the distinction is important. “We’re all so different-I could never play the parts Claire Danes plays, and I don’t think she could play the parts I play. And Natalie Portman plays totally different emotions than I do.” So if she’s always passed up for the ingenue roles and typecast as the knowing young rebel, Ricci’s OK with it; if the emotions she’s known for are anger, frustration, and unbridled lust, so be it. It’s not clear whether she’s referring to the serious-minded Danes, heading off to Yale next year, when she explains why she’s not going to college: “All these other actresses who go off to college are way too annoying.

It’s just not something for me. I’d probably get kicked out. And then my publicist would be upset because everyone would find out about it.” Lest we worry too much about Christina Ricci, it’s only fair to say that she’s still a little embarrassed by certain sex scenes, like the one in Pecker. “I had to make noises in looping,” she says, “and I was like, ‘There’s no way in hell I’m making any noises.’ And John was like, ‘Mmm-hmmm.’ He thought it was a riot.” And, she’s quick to point out, not all her upcoming roles are young nymphos. “In Desert Blue I don’t have sex,” she says reassuringly. “I’m much more into bombs than sex.”