The Guardian – December 26, 2022

Coco Khan

December 26, 2022

When I was a teenager and first going to gigs, I was told an unwritten rule: never wear the T-shirt of the act you’re going to see. So, I thought long and hard about whether to wear my T-shirt of Christina Ricci (as Wednesday Addams) to my interview with Christina Ricci. We’re due to discuss her far more recent role as Misty Quigley in the macabre survival drama Yellowjackets, when the T-shirt question is taken out of my hands: her publicists insist our video call be voices only. But as I soon learn, Ricci is not someone with whom rules hold much sway. “Rules” suggests definiteness, yet defying other people’s definitions has been her lifelong career, and even in our interview – as I press my questions, trying to get a sense of her – she eludes it. “I love chaos,” she muses at one point. Yep, I should have worn the T-shirt.

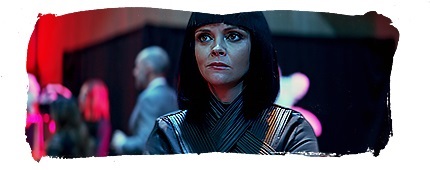

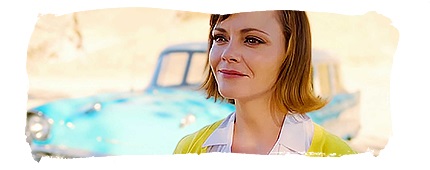

When we connect, Ricci, 42, is in the middle of shooting season two of Yellowjackets, which this time around sees Elijah Wood (Lord of the Rings) and Lauren Ambrose (Six Feet Under) join the cast. “Reading the first two scripts, I was shocked,” she says. Which is saying something, given that season one followed a girls’ high school soccer team descending into cannibalistic tribes when their plane crashes in the wild. Ricci plays the adult Misty – a quiet, unpopular kid who finds that the wilderness gives her the social cache she always dreamed of. “So many people will say to me, ‘I am Misty,’” says Ricci. “It’s interesting that people relate to such an extreme character, and that feeling of not being accepted, of feeling alone.” Ricci was instantly intrigued by her. “I’m extremely interested in deviant behaviour,” she says, “and what happens to someone when they feel very small – the pettiness, the control – especially in terms of how it relates to women’s experience.”

While mainstream audiences may be riding the wave of “unlikable” women only recently, Ricci has been at the vanguard for decades. Beginning her career as a nine-year-old, it was her breakout role as Wednesday Addams that propelled her to stardom, playing the pigtailed icon at 11 and 13 in the Addams Family films. Wednesday is currently being rebooted by Netflix, with Jenna Ortega in the titular role – though Ricci also appears. Is it weird for her to talk about Wednesday? “I don’t mind. I talk about her in almost every interview!” she says. “But I think it’s important to note that this new Wednesday is different. Today’s young people deserve to have their own version of Wednesday.”

After playing Wednesday, Ricci’s star continued to rise as she moved into more adult-oriented parts. There was Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow, and Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm, in which she played an angsty teen ruining Thanksgiving dinners with lines like: “Thank you … for letting us white people kill all the Indians … and stuff ourselves like pigs, even though children in Asia are being napalmed.”

Throughout this time she was living in the maelstrom of 90s celebrity culture – a brutal period for young stars – providing an alternative to the perky, peppy ideal.

“I had tons of things written about me that were disgusting,” she says. Which may explain why she would sometimes give hostile and inflammatory interviews, including once saying it was fine to sleep with your parents. I mention Britney Spears as an example of the toxic treatment of young women. “I knew her,” she sighs. “She was very kind. It was all so horrible and unfair.”

Are roles better for women these days? Definitely, she says, though there is still “internalised misogyny” to deal with. She points to the language women use for each other, such as the increasingly common use of “bitch”. “When people say to me, ‘Oh what’s up, B?’ I will say, ‘Unless you’re going to rape me or beat me, please don’t call me a bitch.’”

I ask her about fame in youth. It must have been traumatic, I offer. Not really, she says. “At the time I was allowed to be rebellious in a way I don’t think a lot of other young women were. And there was no internet then. So I really slid through the whole thing.

“People write things like: ‘Christina talks about the trauma of fame,’” she says, sounding frustrated. “It’s like, ‘No!’ When I am talking about childhood trauma, I am not talking about the trauma of fame.”

I want to ask Ricci more about the trauma she is alluding to, to find out if it relates to her oeuvre. After all, the first films I got into as a teenager were dark, scary movies, and years later – when I was trying to process the painful things that happened in my youth – I read a study that said such movies had been shown to help people process trauma. But when I try to talk trauma, I can feel a resistance.

I tell Ricci that whenever I had previously heard her allude to childhood trauma I had always thought it might relate to sexual harassment or sexual violence. “Was I wrong?” I ask.

“Yeah … ” her voice falters. “I’ve had a many … varied … I’ve had a … there have been a lot of things, but that’s not what I’m referring to,” she says.

I can’t see her face. I’m wondering if she wants to say more.

“There’s been childhood stuff. Child abuse in my family.”

This isn’t the first time Ricci has mentioned abuse, per se – in 2019, she said in an interview with the New York Post: “I feel it’s child abuse to make your kid famous.” But as much as I want to find out what she means, and to discuss whether we as audiences need to take responsibility for creating child celebrities, I can tell she does not want to elaborate.

I change the subject. Does she see herself as a role model?

No, she replies. “I feel just very earnestly that I’m a person trying to do the right thing. I don’t think you’d want to model yourself after me. There could be a few cautionary tales in there.”

Looking back, does she have any regrets?

“I regret everything!” she says. “I’m probably the only person who’ll be honest and tell you – if I could do it again, do it over, I’d do it a better way.” How so? “OK I’m being glib. But it’s an overarching feeling.”

Now it feels like the more we talk, the more my shape of her loses definition. I ask: do you feel that you get to be authentic, or are you always performing?

Authentic. “Though I’m a strongly opinionated person and sometimes I can’t say those opinions. So I am aware of times when I don’t necessarily say what I mean.

“But I have a lot of people taking care of me, who encourage my authenticity and don’t control me, which I dealt with a lot when I was younger.”

I ask her about the celebrity world’s obsession with youth – it must be especially acute if you were famous young. “In my mind, I look the way I did at 27,” she says. “I have this very nice filter over myself. So looking at realistic pictures all the time is a little bit of a mindfuck. I’d love to just go through life believing this delusion that I still look 27. It wouldn’t harm anyone!”

But even with the existence of the internet, Ricci seems optimistic about the future youth, especially when talking about her children: she has a one-year-old daughter, Cleo, and an eight-year-old son, Freddie, who “won’t be able to avoid” being a progressive young man.

“My husband, Mark, is, I hate to say it because it sounds really obnoxious, a feminist. And Freddie is going to see that, and see his working mother. I think he’ll see women in a much more layered, complicated way, just by having grown up watching his mom do all this stuff.”

She tells me how Freddie’s childlike questioning has helped her see her own blind spots – perhaps the internalised misogyny she spoke of earlier. “He’s asking questions like, ‘Mom, is that racist?’ Or, ‘Mom, is that OK for women?’ He’s got this whole thing about not calling objects – like boats – she. He’ll correct me: ‘Women are not objects.’”

Has motherhood changed the sorts of roles she wants to do? “I would never be able to play someone who is mean to a child. I can’t even read it if it’s in scripts. I have a lot less ability to handle extreme misery.”

But wait, Yellowjackets is violent? “It is,” she says. “But it’s horror. That’s different.”